What happens when you write “about” someone as a part of your own personal experience? What happens when you live in a place and feel suffocated by the norm? What happens when you name a problem in a society that is not yours? What happens when that society envelops you and includes you (and therefore excludes you)? How do you move beyond any sort of liberal paralysis that tells you not to speak for others, that you are only a guest in this context, yet you're lead by a gut feeling that something is wrong? And how do you say in Arabic, “It was never my intention to cause any harm”?

Read MoreArabic

Solitude /

My body does not feel my own. I do not feel my own. My smile falters, my voice fades, and I feel trapped. I cannot walk on the streets alone, I've been told by my host mom. I cannot travel alone, I've been told by the program. I cannot sit in a café alone, I've been told by Moroccan friends. The world started to close in: I have school, the classroom, the garden outside of school, the tense ten minute walk home, and the house. The house is lovely and commanding and reeks of mold and the pressure of a hospitable host mother who is constantly telling me "Eat! Eat!" I do not have a room of my own, I'm starting to go mad.

Read MoreJordan الأردن /

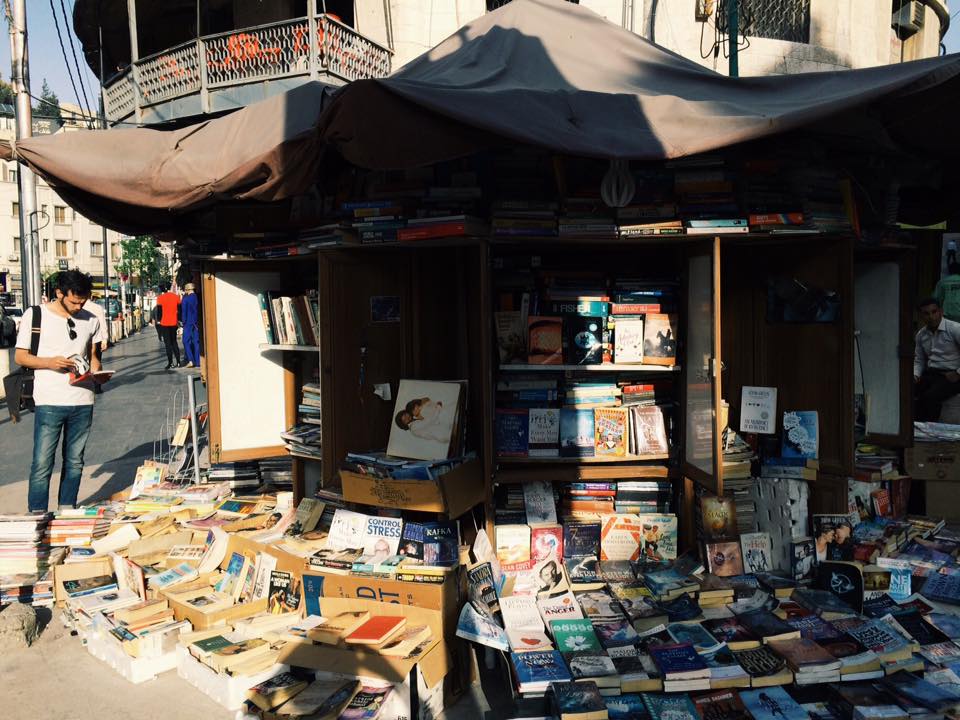

Last week during the Pesah holiday in Israel, I travelled to Jordan: from Bayt Shean and Irbid in the North to Aqaba and Eilat in the South. I saw the Sea of Galilee and the Golan from the other side. I dipped my toes into the Red Sea and waved to Saudi Arabia. My days were punctuated by the call to prayer (from its excellent reverberations in the hills of Amman to the transitory notes of someone’s cell-phone ringing an alarm while on a bus heading South). The experience is already slipping away into a mirage tinted in tendrils of Orientalist sentences that romanticize an exotic and foreign life of deserts and tea and hospitality and tribal connection.

There has been a long-standing joke between my parents, Tina, my best friend from high school and myself. One summer, I was 19 and studying Hebrew in Jerusalem, a friend of a friend was living in Amman and I suggested that I might travel to Jordan to meet him. The idea was met by outcries from my parents, “No way. You barely know the guy. You can’t go to Jordan.” They then turned to my friend Tina, tall, blonde, of Norwegian descent, looking like a Viking, “Tina, can go to Jordan. Sophie should not go to Jordan”

Over the years this joke has reared its head again and again, “Sophie can’t go to Jordan.” My friend has even had dreams where she came to visit me in Jerusalem, and then went to Jordan, but I wasn’t allowed to cross the border with her.

As a student of Middle Eastern Studies, I have to confess that this was my first time in a fully Arab and Muslim country. My degrees focus on Israel and Palestine, my languages relate to Israel and Palestine, my experiences are mainly rooted in Jerusalem. My relation to the places outside of this bubble has always been shaped by the Jewish and Israeli identity that held me back. You—with your Jewish curls, your Israeli passport, and your feminine naïveté—you are not allowed to travel alone in “those” places.

This sentiment was echoed again this year as I told people about my plans for the Passover holidays.

“Jordan? Why?”

“Jordan? Alone? Are you sure?”

“Jordan? It’s not safe.”

Surprisingly enough, this time around my parents were not against me going, or at least they knew better than to tell me. At the moment, Jordan is the most stable and safe country in the region. It has turned into the hub of internationally based students of Middle Eastern Studies, NGO workers, volunteers, UN interns, and more. Since the rest of the region is off limits, those who used to go to Cairo, Damascus or Beirut to study Arabic are now all go to Amman. I have 3 friends there currently, including one of my close friends from my undergrad and another from my Masters program.

So with that in mind, I packed my bag, and headed up to the Northern border. There are three land-border crossings between Israel and Jordan. One is up North, the Sheikh Hussayn Crossing, about 2 hours from both Jerusalem and Amman. The main border crossing, Allenby Bridge, is located about 40 minutes from Jerusalem and Amman. This crossing is the only place where Palestinians without passports (i.e. those from the West Bank with laissez-passé documents) can cross in order to use the Amman International Airport. Israelis are forbidden from using this crossing. The third crossing is down South, the Yitzhak Rabin Crossing, where Aqaba, Eilat, and Taba hug the coast of the Red Sea and compete for scuba divers and tourists.

Getting to the border was a journey of its own. After five hours in transit (and three separate bus changes), I found myself in (what felt like) the middle of nowhere in Bayt Shean. I flagged down a cab and asked to be taken to the border. No other options in sight (with a bus that goes from Bayt Shean near the border only a few times during the day), cabbies charge you for your desperation. 5 minutes later, he had dropped me off at this strange strip where I followed mazes of signs indicating where pedestrian travelers are supposed to walk. As I entered the air-conditioned doors of the building, I looked lost and was quickly guided by a man in Hebrew to the proper windows.

"Traveling to the East?" he asked me in Hebrew, scanning over my backpack and assuming that I was making the pilgrimage to India that most Israelis my age make after completing their army service.

"No, to Amman."

"To Amman?" he repeated as if to make sure he heard me correctly. "Amman?" he repeated a second time.

I smiled and walked on to the next window to get a stamp in my passport and move on.

I got on yet another bus that drives across 200 meters and an imaginary line that has been drawn in the sand between the two countries. Jordanian border police greeted us and the regulars (young Palestinians with Israeli passports) walked in a quick diagonal towards the doors of the customs office, familiar with the shortcuts. I exchanged shekels for dinars and paid the entrance fee. Once you emerge, you find yet another cab to take you to the edge of the border. I was squeezed into a cab with 4 young Palestinians in the backseat, a trunk that wouldn't close properly, and a cabbie who looked at me and said "American? America is good." And with that, I walked through the looking glass and into another identity.

The whole week in Jordan, I felt comfortable in my own skin. As an American, as an Israeli, as a Leftist who says the words occupation and Palestine louder than a whisper, even as a woman. The stereotypes and fear mongering that had prevented me from making this journey sooner were quickly dispelled by smiles, rooms filled with cigarette smoke, and cups of black tea with I-don't-want-to-know-how-much sugar.

The little spoken Arabic I have learned (and the old-fashioned literary Arabic I learned at school) made a huge impact in interactions and I was surprised again and again by just how much I understood. At one point a friend explained their language level perfectly. "I speak dictionary," he responded to a conversation about whether you speak spoken-Arabic or literary-Arabic. Dictionary-Arabic is what they taught us in Jerusalem too: how to break down sentences, how to analyze grammar, how to open a dictionary and translate. But during this week, the words of the dictionary pages came to life. Idioms such as Inshallah, Wallah, Ma-shallah, El-hamdulillah and more entered the gaps in my sentences. Encouraging grunts of "uh" filled the pauses between my breaths. Sighs of contentment and tasty meals soon had new adjectives to describe them.

The adventure truly got underway during my first night. After being scooped up at the border by my friend and his rental car, we braved the lawless traffic and roads of the North. We headed to Um Qays, a hilltop covered in Hellenistic ruins and a Roman amphitheater carved out of the black basalt stone. We ate lunch overlooking the Galilee and the Golan. After a good meander through the fallen columns, we went back to the car to scan through the guidebook and pick a place to stay that night. My eyes landed on a place called Pella, a small town about an hour away that was supposedly surrounded by ruins from every time period extending from Neolithic to Umayyad, Abbasid, Hellenistic, and Byzantine; plenty to explore tomorrow. So we called up the Pella Countryside Guest House and asked for a room for 2.

Along the way, we passed near the border and standing in the dark at the side of the road were three figures with big backpacks: tourists. Before I knew it, my friend had pulled to the side and offered them a ride. Three sweet-faced Germans, volunteering in Israel and on vacation in Jordan, climbed into the backseat.

They smiled warmly as they announced that they were looking for somewhere to camp. We mentioned where we were headed and offered that maybe they could camp in the land near the guesthouse.

Upon arriving to Pella (also known in Arabic as Tabaqat Fahl), after many detours and young children running up to the car and pointing us in the right direction, we turned onto a small road following signs for the guesthouse. A man was standing in the middle of the road, waiting for us it seemed. Turns out it was the owner of the Guesthouse. Hellos were exchanged, we confirmed that we were the ones who called for the room earlier, and we had some more people now, could they camp?

It was quickly and clearly seen not to be an available option.

“My brother. My sisters. You should not camp here. Not with everything going on in these parts.”

One of the Germans timidly looked over at my friend and me, “Does he mean that there has been a murder here recently?”

We laughed and shook our heads. “He’s talking more generally about the Middle East as a whole.” What we didn’t say was that it also was directed at the prospect of having another 3 people take a room at the guesthouse during these times of low tourism—because you know, everything that’s going on around here lately.

The evening was punctuated by intense political, religious, and theoretical conversations with our host. The place was less hotel-like and more personal: “What you eat, I eat. What I eat, you eat. When do you want dinner?” asked our host.

We gleaned a lot of information from him, not only about the current status of political affairs, but also of what life for a Jordanian is like. He had been in the air force, he had seen some horrible things during Black September, he was an ardent supporter of His Majesty King Hussein. He was eager to share universal quips about how all people, be they Muslim, Christian or Jewish, should be treated with equal dignity. He bragged about how Pella was a favorite place of Jesus Christ (who by our host’s version of history had visited four times). He went on about the beauty and the importance of all human life.

“Except for the Saudis. And the Kuwaitis. And the Shi’as. They are not Muslims” he confided.

By the end of the stay we were pretty convinced that he has serious government connections. Our suspicions were confirmed the next day. Over dinner he had spoken of how there was a hidden cave, where Jesus is said to have stayed, and an old Byzantine church that no one ever visited. He took us there the next morning, pointing the route, waving at every person whom we drove by in recognition.

After letting us roam freely among mosaics and Byzantine sarcophagi, he directed the car into town to buy cabbage for his wife. We pulled over and let him into the store. He returned to the car and then said, quite casually, “We’re right across the street from the head of the Municipality’s house. Why don’t we pay him a visit?”

My friend and I exchanged worried glances, but how could we say no to our host who had been so gracious?

So we followed him like sheep into this government building, first my Arabic speaking friend, then me, then the three Germans. We were ushered into a room and as the cigarette smoke cleared, I saw a man sitting behind an impressive desk, framed by a tapestry on the wall behind him with the bismillah embroidered in gold thread. The walls of the room were lined with brown-leather EZboy recliners. Sitting in those chairs were nine men smoking cigarettes, including one man in full Bedouin garb smoking a giant rolled cigarette. Another man was wearing the clean-khakis of casual army wear. They looked as if they had been waiting for us. Our host glided into the room with ease, sat down and took the cup of coffee proffered to him by a young man. Salaam-alaykums were exchanged, and then our host dived into a speech. The Germans and I smiled to each other nervously.

Translations muttered under my friend’s breath alerted me that our host was asking the government official for a road out to the church that we had visited that day. Tourism. Tourism could be a big boon for the district, if only there was a road and someone taking care of this church. Look! These tourists crossed over from the Northern border and arrived here—he gestured at us sitting there. With a proper road, we could have tourists like this all the time.

The man sitting behind the desk listened. He then returned a speech with many gestures and seemed to take the upper hand quickly.

“Who am I to deal with tourism? There are many different ministries that are responsible for that.”

The conversation continued as two little cups were passed around, refilled with coffee, and passed to the next person.

As abruptly as the whole thing began, it ended. We said goodbye and walked out and down the stairs. We paused at the entrance to the building and our host smiled at us: “You did good for Jordan.” And with that we got back in the car and drove off.

The rest of my visit to Jordan continued in a similar strain: individuals opened their homes to me in an incredibly personal way that offered me glimpses into so many different ways of living.

From Amman and my circle of expat friends who cringe as they realize that they are “gentrifying” a certain neighborhood yet can’t imagine living anywhere else in the city, to the warm welcome from my two Jordanian friends who snuck me in as a local resident to see the view of Amman from the Citadel, to the best scrambled eggs of my life in the cave home of our guides in Petra, the week was full of moments of intense hospitality, authentic conversations, and an intimate feeling of trust between strangers. That combined with the spectacular scenery and the strange feeling of déjà vu as we walked through the ruins of several Empires’ histories, while the region around us is collapsing all over again, made the week an unforgettable trip.

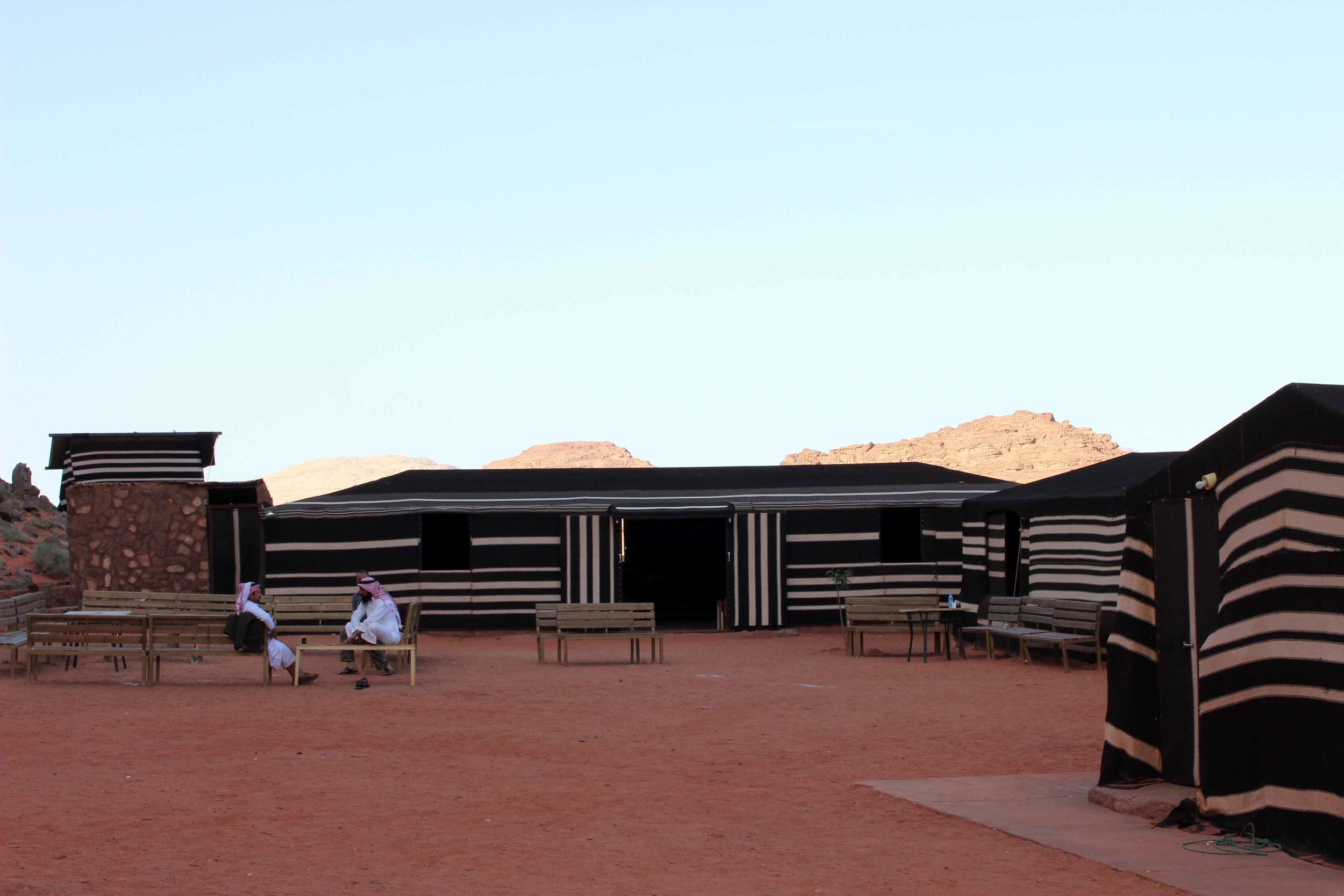

On my last day, I stayed behind in Wadi Rum for another hike with our Bedouin guide as my friends from our camping trip returned to Amman. We explored local corners, his favorite spots, climbed up rock faces, and searched for the most impressive views of the 700km of desert around us. He took me to a quiet mountain well, with clear, cold, fresh water and as I splashed the water on my face to wash away the dust, I felt a quiet that I have never yet experienced.

As we left the spring we ran into yet another jeep and two tourists got out. A young woman and I smiled at each other, asked where we were both from, and quickly switched to Hebrew as we realized our homes are both in Israel.

"You're here alone?" she asked. "You're not scared?" she wondered aloud.

I smiled and shook my head and waved as I walked back to the Toyota, sand in the soles of my sandals.

The day was coming to an end and my Bedouin guide helped me call a taxi and made sure that he would take me straight to the border. I climbed into the cab and waved goodbye to Salem, goodbye to the desert, and hello to air conditioning. The cabbie and I chatted in limited Arabic and English: “Where are you from. What do you think of Jordan. The desert is beautiful.”

We were quiet for a moment and suddenly he reached down and started rummaging around the glove compartment. I got nervous. Here I am, alone in a cab, perhaps being too trusting. I began to think that every fear that had been instilled in my head was about to come true on this curving, isolated, highway road. He suddenly turned around and, smiling, offered me a melting ice cream.

My week in Jordan was a welcome wake-up call. According to the 24-hour news cycle, the world as we know it is poisoned and falling apart all around us: ISIS is hiding behind every turn, every stranger you meet may decide to shoot you, and every man is a rapist. In Jordan, I encountered a different reality: one in which humans are being human. Where good people are living good lives and being kind and recognizing the humanity in one another. It was a breath of fresh air and an important reminder. The world can still be kind.

Thyme to Build A Road: Solidarity Action in South Hebron Hills /

It was after the end of prayers and suddenly many young men from the village showed up, pick axes in tow. “The Shabaab will break the ground, you will put in the plants.” We quickly settled into a rhythm, conversations flowing and laughter ringing across the field as we watched row after row of thyme settle its roots into the dirt.

The young man next to me, Omar, swung the pickaxe into the dirt and told me about how he finished his B.A. at Hebron University in Agricultural development and wants to do a Masters in water. I smiled encouraging words as I pushed away rocks and broke up dirt to place yet another thyme plant in the ground. Tariq, another young villager, described what life is like in his village. There's a difference when you read that some villages only receive two hour of electricity to when someone looks you in the eye and tells you this

As the journalist next to me asked Muhammad about the village, I overheard him respond in broken English, “I was born here, I live here, and I will stay here.”

The fierce desire to remain rooted in a place, in the face of so much violent opposition, bureaucratic antagonism, and a prejudiced system almost seems naïve. Yet, existence is resistance. That line has been echoing in my head all weekend.

This weekend, an unprecedented event took place. Over the course of 36 hours, 71 people spent time working in Susiya, Bir el-Eid and Umm al-Khair in the South Hebron Hills in the West Bank.

Here’s the catch—most of those people were Jews.

Read MoreAll For Peace Radio /

I watched a young, tan Israeli woman in a tank top walk out of a recording studio to be replaced by two girls wearing matching hijabs walk in.

Her show was about music in English, Hebrew and Arabic. The Palestinian girls come once a week for training how to have their own talk show. They talked about love and boyfriends.

A place without borders: All for Peace Radio.

Read MoreHumans of Hand in Hand /

I am pleased to present to you, Humans of Hand in Hand: Jerusalem Edition!

Hand in Hand: Center for Jewish-Arab Education in Israel brings together thousands of Jews and Arabs in five schools and communities throughout Israel. They are proving on a daily basis the viability of inclusion and equality for citizens of Israel.

Like their Facebook page and for the next few weeks your news feed will be graced with beautiful photos (taken by yours truly!) and interviews with the teachers, students, and people who work at Hand and Hand and make it what it is.

Support Hand in Hand! It's a wonderful place and they are doing good good work in the face of so much cynicism and violence. Thanks to @humansofny for the inspiration.

Humans of Hand in Hand /

March 23,2015

I spent the day in a utopia. The best part about all of this? It’s real.

I’m volunteering with a mixed school in Jerusalem that is called Hand in Hand. It’s both Arabs and Jews, K-12. The school has been around since 1998 and now has over 600 students.

It’s a public school, and in order to understand just how special that is, you need to understand the Israeli school system. Within Israeli education, there are separate tracks for Arab and Jewish schools. That means different curriculum, different language, separate worlds. This type of school however, is rare. Classes are taught in Arabic and Hebrew, often with 2 teachers in every classroom. They have redesigned their history curriculum to include both narratives and they celebrate and learn about Jewish, Muslim, and Christian holidays. The first class to graduate high school was in 2011.

I spent the day with 3 graduates taking photos and interviewing students, teachers and people who work at the school. We are creating a project similar to Humans of New York, but about the school instead. It will be up on the Facebook page of the school in the next few weeks.

We asked kids questions like, “If you were any kind of food what would you be?” We asked older kids about what it was like for them to come back to school after this summer. Teachers shared what inspired them and the security guard told us he loves cats. Conversation flowed between Hebrew and Arabic without pause.

My favorite moment was when we talked with two 1st graders who’s classroom had been burned in November by extremists (for news coverage of the event see here). We asked if the boys were friends and one said about the other, “He’s annoying in class.” That moment captured for me the beauty of this place. It wasn’t about who was a Jew and who was an Arab. They were just normal 1st graders. But it was also normal to be asked a question in Hebrew and respond in Arabic or vice versa. It was normal to grow up with friends who are different than you. It was normal to have friends who live across the invisible lines that zigzag and cut through this city.

The school is idealistic and may be a bubble, but it is a beautiful bubble and a great place to start. For more info look up Hand in Hand: Center for Jewish-Arab Education.

Passion, Responsibility, Action: A weekend in Beit Jala /

March 15th, 2015

I spent the weekend at a conference with Palestinians and Israelis in Beit Jala, a place only 15 minutes from Jerusalem that sits at the confluence of roads that lies in the space where Israelis and Palestinians both have permission to be. We stayed at a hotel called the Everest, and as we climbed the hill to the very top, it was clear why it was named such.

It was an incredible weekend; there were Palestinians from all over the West Bank near Nablus, Ramallah, Bethlehem and Hebron. Israelis from Jerusalem, Hadera, Sderot and the north. We began the weekend by sharing the thing that is most important to us: family, freedom, silence, music, learning, an end to occupation, peace.

I befriended a young Palestinian from Jericho who plays classical guitar with fingers plucking notes like water. He shared how he can't meet his friends in Haifa because he doesn't have a permit to travel and the frustration he feels being 21 and not able to go 45 minutes away from home. I listened as a young Israeli described how she couldn't return to her work for 2 weeks after a rocket had fallen near it this summer. An older Palestinian from Bethlehem described his experience as a 15 year old when the army would not let him return to his home during a curfew and after making him take the long way around, arrested him. I listened as another Israeli described a moment meeting a Gazan and acting as his legal companion to satisfy permit requirements to reach Jordan. The Israeli shared how it was the Gazan's first time out of Gaza in his entire life—he hadn't seen an orange orchard since he was little. The Israeli took the long way to the Jordanian border with a stop in Jerusalem so that this Gazan could visit al-Aqsa. I sat at breakfast with a Palestinian whose family is originally from Gaza. He described how 15 members of his family died this summer. 11 of them died at the same time when their house was flattened. Yet he continues to come to these meetings. His eyes sparkle when he laughs.

Brought together to share these heavy personal stories, I was surrounded by a lightness. Here we were, a strange mixture of Arabic, English, Hebrew, and patient translations, coming together to talk, to listen, and to be heard.

The second day was devoted to brainstorming sessions: what projects could we create together, what ideas did we want to put into action? Ideas ranged from language exchange, to fundraising for a center for disabled children, to starting a running group and organizing a marathon from Tel Aviv to Ramallah, to trying to humanize the news and remove media bias. Past groups had created Tiyul Rihla, an organization that takes Israelis and Palestinians on tours of historical sites and shares both narratives and Two Neighbors, a fashion line that incorporates Palestinian embroidery in high fashion and is sold in the States. Our ideas were big, yet we broke them down into small steps such as exchanging each other's email addresses. The main goal was to commit to meet again.

I left the bubble from this weekend and I feel hopeful. I am now faced with so many opportunities and new beginnings, new friends and new experiences to come. The weekend was invigorating and inspiring. Good things can begin with something small.

Elections are in 3 days. Hold your breath, knock on wood, and do whatever superstitious ritual you have for good luck. We need it here.

To learn more about the organization that hosts Global Village Square Conferences, click here.