I was slowly walking up the hill to my apartment, sleep-deprived after a few dusty days and nights at Sarura, carrying a backpack and the scent of wood smoke in my clothes and hair. A man was standing at the corner, at the top of the incline. He smiled, uninvited, and asked in Hebrew:

?עליה קשה Aliyah kesha? [Hard climb?]

It might have been the general exhaustion or the heaviness of his question that led me to shake my head yes and shrug my shoulders as in defeat. He motioned to my backpack and asked, in that tone that only strange men who want to engage in conversation with a lone woman on the street have,

?רוצה עזרה Rotza ezra? [Want help?]

To which I shook my head defiantly, smiled, and said, "No, I'm strong."

In Hebrew, the word la'alot has many different connotations. It means to rise up: you use it when talking about alighting on a bus, about climbing a hill, about achieving another level, about arriving specifically in Jerusalem, and also it is the word used to describe a Jew who has immigrated to Israel. The rationale for the later use is that by arriving in the holy land, your soul is rising up closer to a level of spiritual enlightenment and communion with God. However, the use of the word has by and large lost its religious meaning amongst day-to-day use when describing Jewish diasporic immigration to Israel.

Three years ago, I made the decision to olah to Israel.

My mother applied for my Israeli passport for me before I could walk—she took me along when I was only six months old to introduce me to the family—but my citizenship was not "active." My interaction with my Israeli citizenship was limited to the vague memories of standing in a different customs line at the airport in Tel Aviv than my dad who lined up with other non-Israelis. A few weeks before I turned 18, we were finalizing forms for my college registration and my mom suddenly said, "Oh! We should get you that exemption from the army!!"

For a split second I felt the different life path if I had been living in Israel. Rather than going to college, with the glimmering nearness of independence and learning and new friends and adventures, I could have been entering the Israeli army. Yet, since I had grown up in the States, the idea was ephemeral and quickly brushed to the side; I never was called to serve.

At age 19, I came to Jerusalem to study Hebrew for the summer on a grant from my college. It was my first time visiting my family in 6 years, my first time engaging with them as the young adult I was becoming, and my very first time able to connect with them in their own language and words.

The summer was transformative; I felt deeply that I had found a place where I belonged. People looked like me, people danced like me, people were intense like me, and my heart felt full to finally be in the bosom of the tribe of our large, loud, and loving family. Having inherited my mom's dual-citizenship, I grew up with a foot in two different places. I was seeking to unify the pieces of our lives and our families.

Since that summer, I continually tried to find ways to come back for extended periods of time: another summer on a grant to study Zionism, another winter studying Hebrew, and finally my MA studies in Jerusalem. Each time I visited, it felt like more than a visit. The place spoke to my bones, there was something there that I was supposed to learn, connect with, and do. Life in Israel is in high-definition; it's almost as if living in the US had been 2-D and Israel was 3-D; colors are brighter, tastes are more tasty, every day feels filled with meaning. I felt like I was finally awake and truly living.

It would be reticent of me not to also admit that I felt naively capable of making change. Of making an impact beyond my own circles and friends. Having grown up with Building Bridges for Peace, an American organization that brought together young Palestinian and Israeli women for 3 weeks of dialogue in the Colorado Rocky Mountains, I had grown up knowing that there were two peoples and a conflict and I was taught that the solution was for the two sides to meet and talk. The founder of the organization was a dear family friend and a mentor to me. She challenged me when I told her that I was going to move to Israel. She asked me,

"Are you going there to become a part of the system, or to change it?"

I responded, in a burst of tears, "To change it."

So, June 2014, I packed my bags, held onto my immigration papers that claimed my status as a "returning citizen" and I “rose up” to Israel.

I was welcomed as a new immigrant, an olah hadasha. My life the first few months was preoccupied with making sure my aliyah was smooth and daily struggles with Israeli bureaucracy: opening up a bank account, sorting out taxes, applying for health insurance.

Then, only a few weeks after my arrival, the war with Gaza began.

The summer was traumatic for me—both in experiencing violence, war, and death up close and also in suddenly feeling a deep rupture with the State of Israel. For so long, I had wanted to move and be a part of the culture, the society, the citizenry. And yet, suddenly I was faced with a situation (in my mind) of unjust retributive violence surrounded by a populace that was frightened and unable to encounter the humanity of the "other," and ineffective politics that used that fear to justify actions and atrocities.

I wanted nothing to do with it.

That rupture was painful, beyond what I was able to admit for many years. It pushed me to want to pack my things and leave. I felt lost and alone.

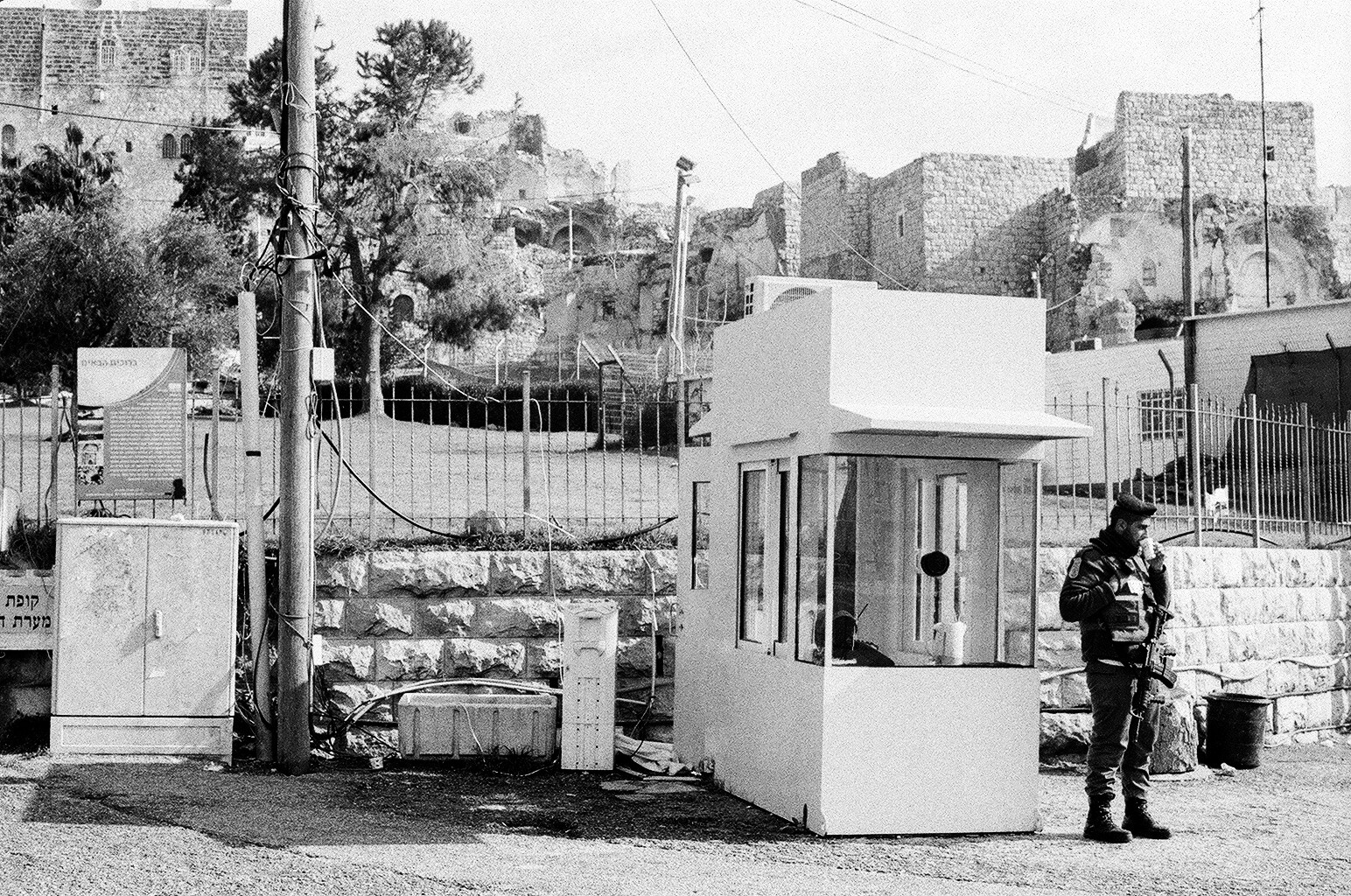

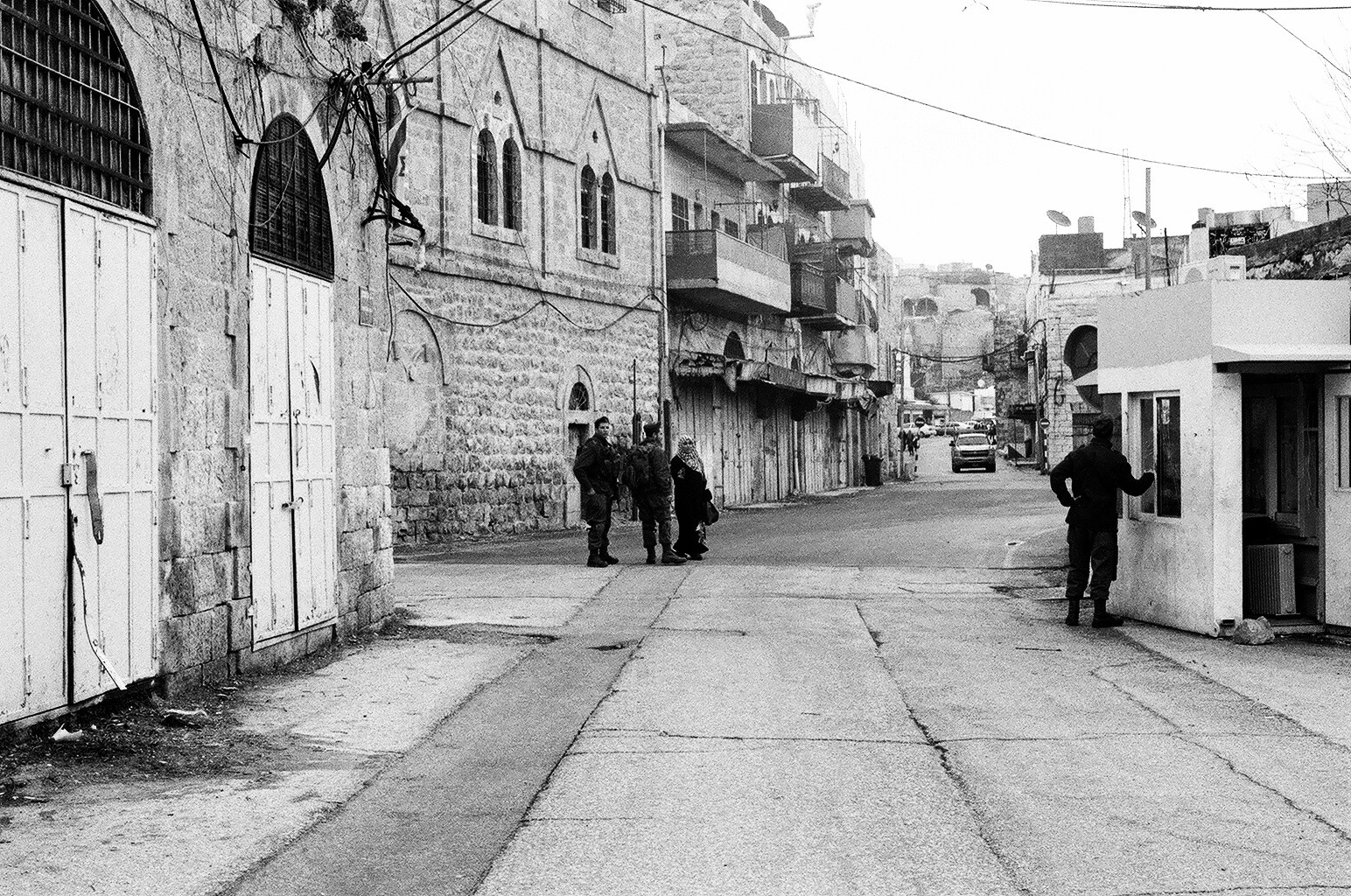

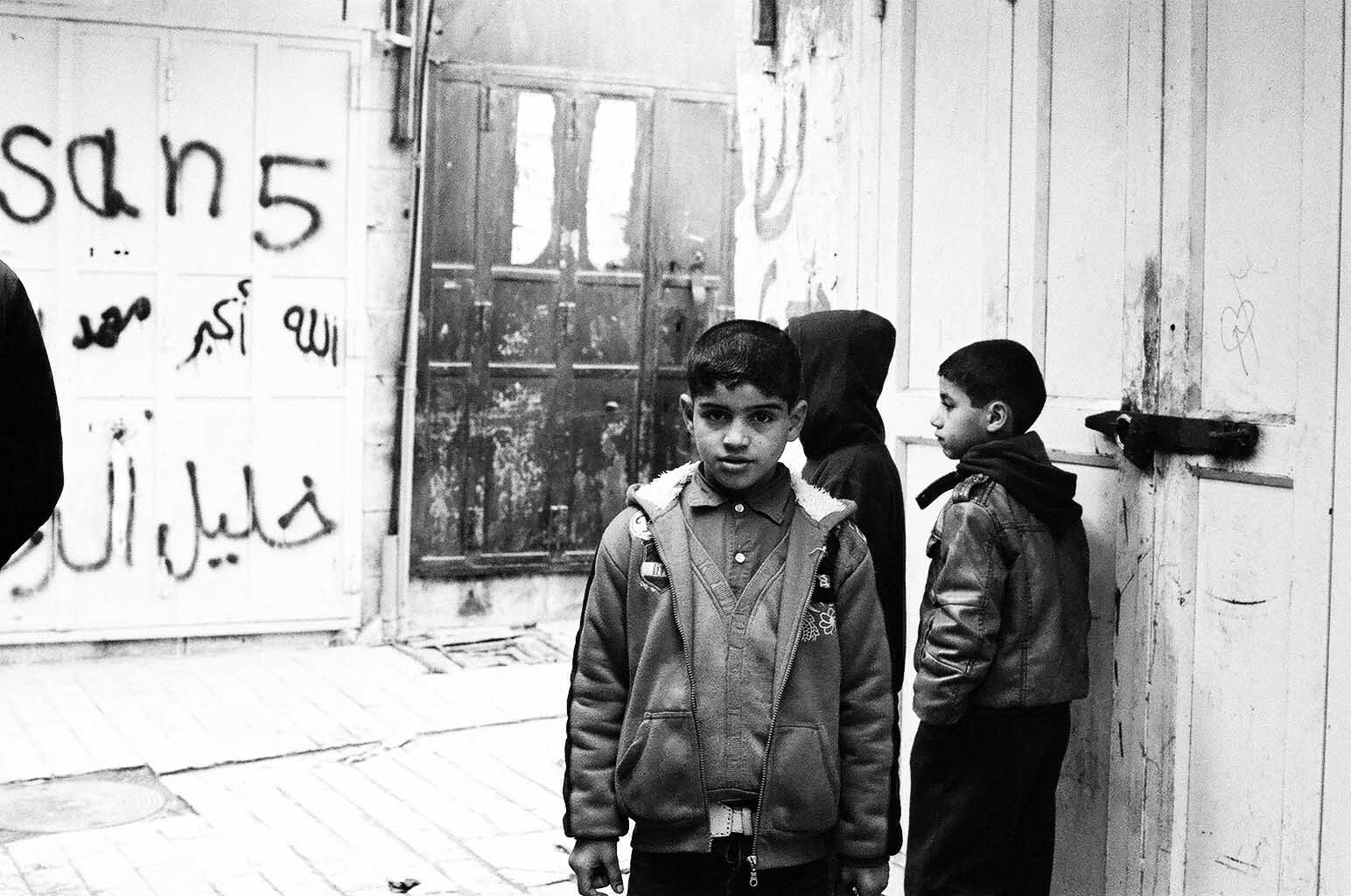

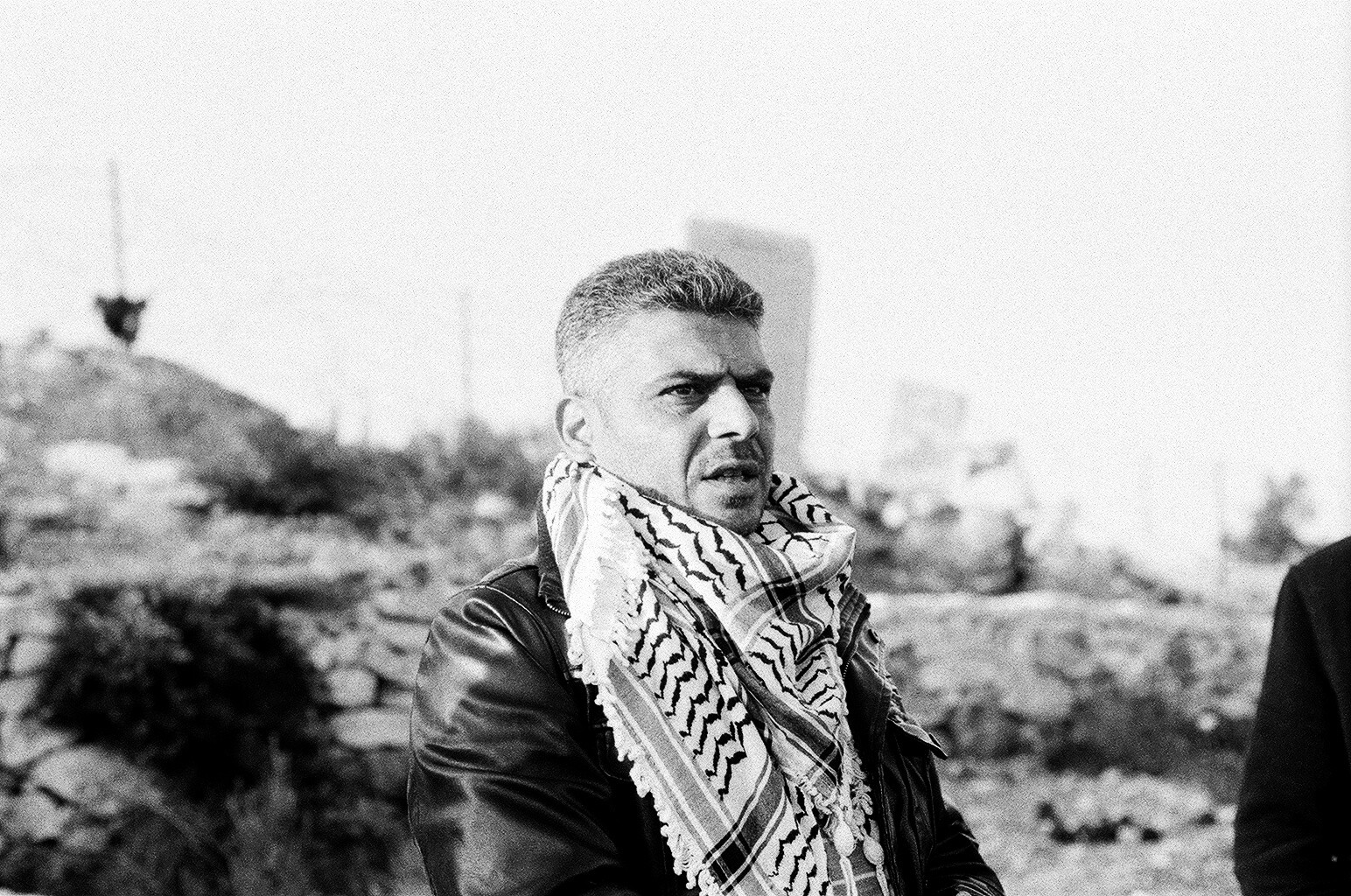

Then, in January 2015, I went to the West Bank for the first time on a tour with Extend. I walked through the ghostly quiet streets of Hebron where Palestinians are forbidden to live or even walk, I met the activists of Nabi Saleh village and held rubber bullets and used tear-gas canisters in my hand, I held the green-identity card of a Palestinian man who shared his story with us and explained the ways that green card limited his movement and freedom to breathe. I learned about the intricacies of military law and courts and the daily occurrence of children being arrested: I heard how occupation is not just about occupying a land, but occupying the minds of a people.

My life went from 3-D to being 4-D. I reconnected with the reasons I had come to Israel beyond family and belonging. I came motivated by a belief that human connection overcomes walls, that seeing things for yourself challenges your assumptions and leads to space of authentic learning and transformation. Hearing the personal story from a person is powerful, and learning to hear stories, in their original language, became an important part of my life. I had found my purpose. I connected with a community of local activists; I was challenged to think differently, to see differently, and to step outside of my comfort zone.

Everything shifted then. I felt challenged and had much to learn, and learn I did.

I am currently sitting on the plane and typing this entire post on my phone as I head back to the United States. I am leaving now because I reached a point where I feel, yet again, that I have so much to learn.

I am leaving Jerusalem because I am starting my PhD focusing on the impact of conflict on female political agency at the University of Denver this September. This path of studying is a continuation of the conversations that began in Israel and Palestine, and I am excited to return one day with more tools and new frameworks to challenge what we think to be true. The movement is only beginning to grow now, the seeds have been planted and I am excited to see what it will grow into next.

Was it a hard Aliyah? Yes.

But, I am strong.

If I learned anything from these years living in Israel and Palestine, it is that.

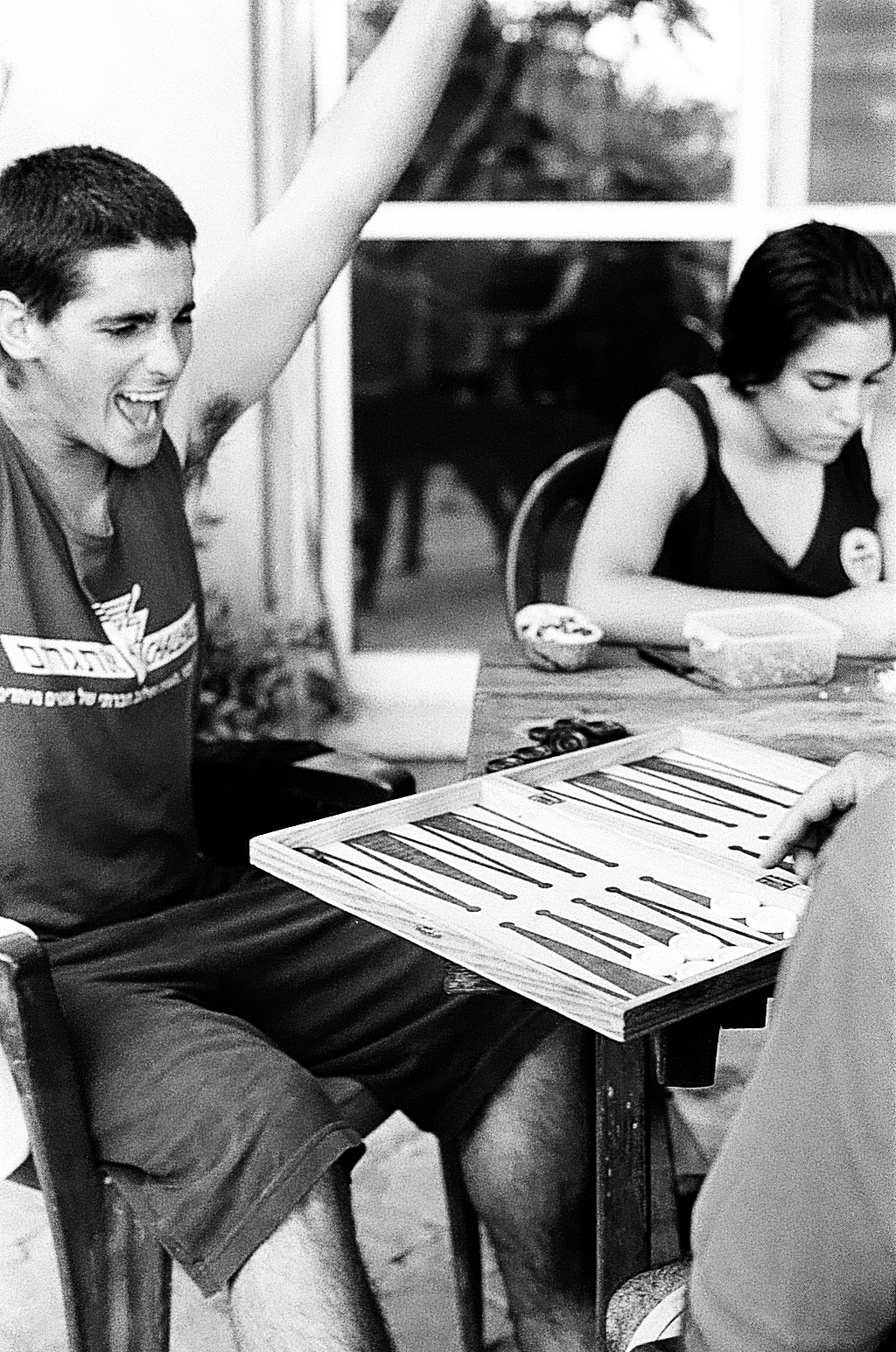

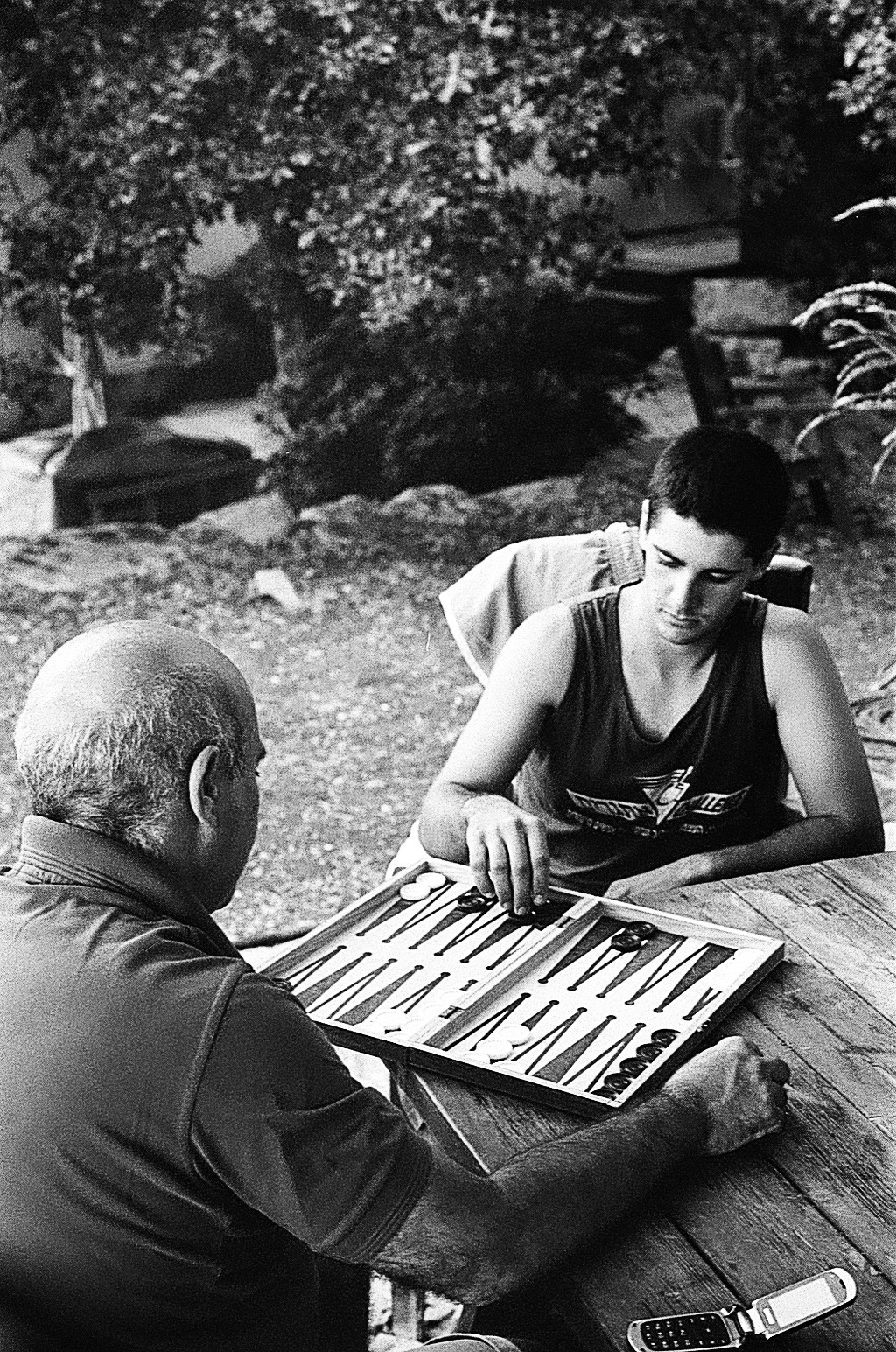

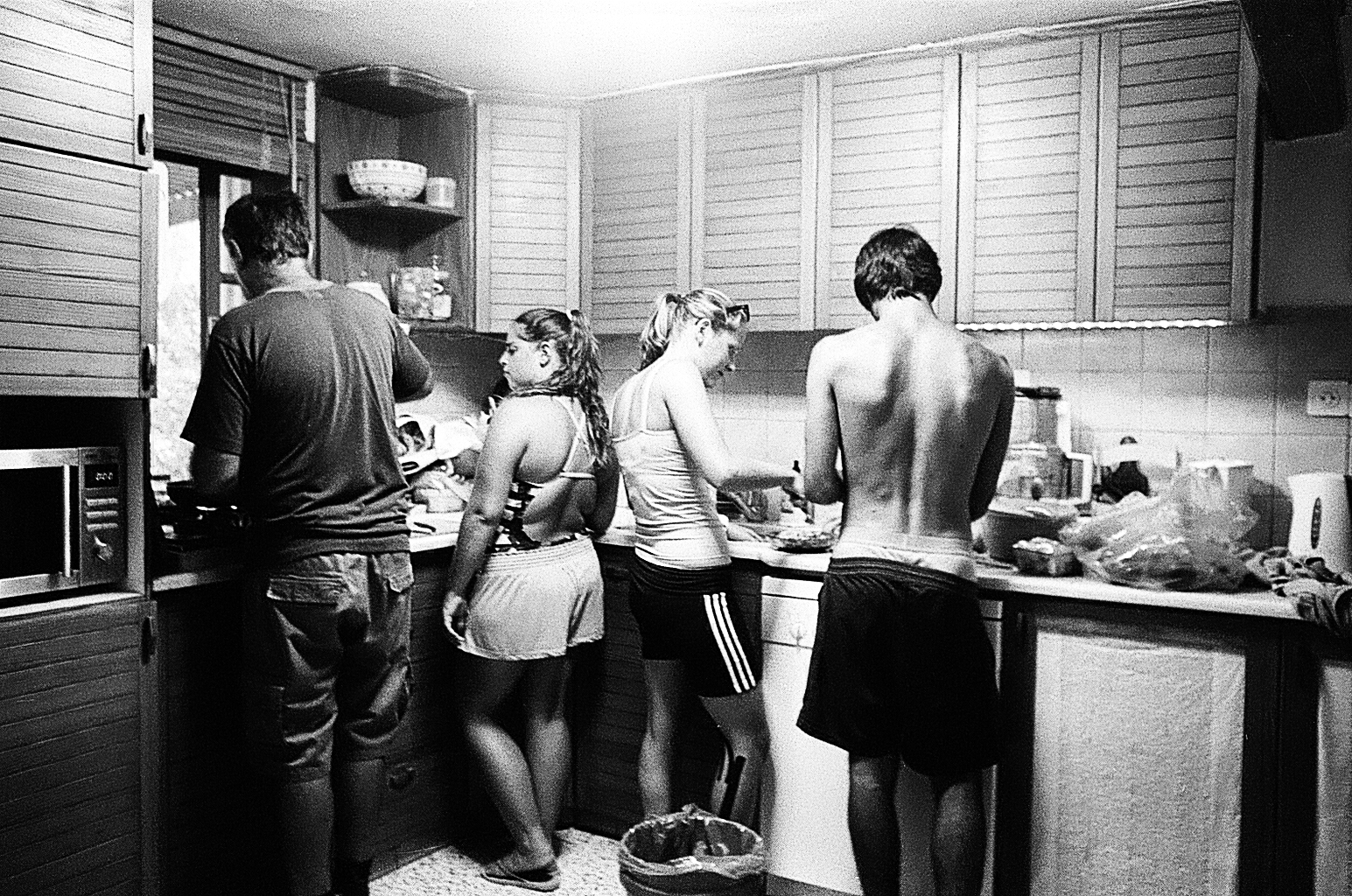

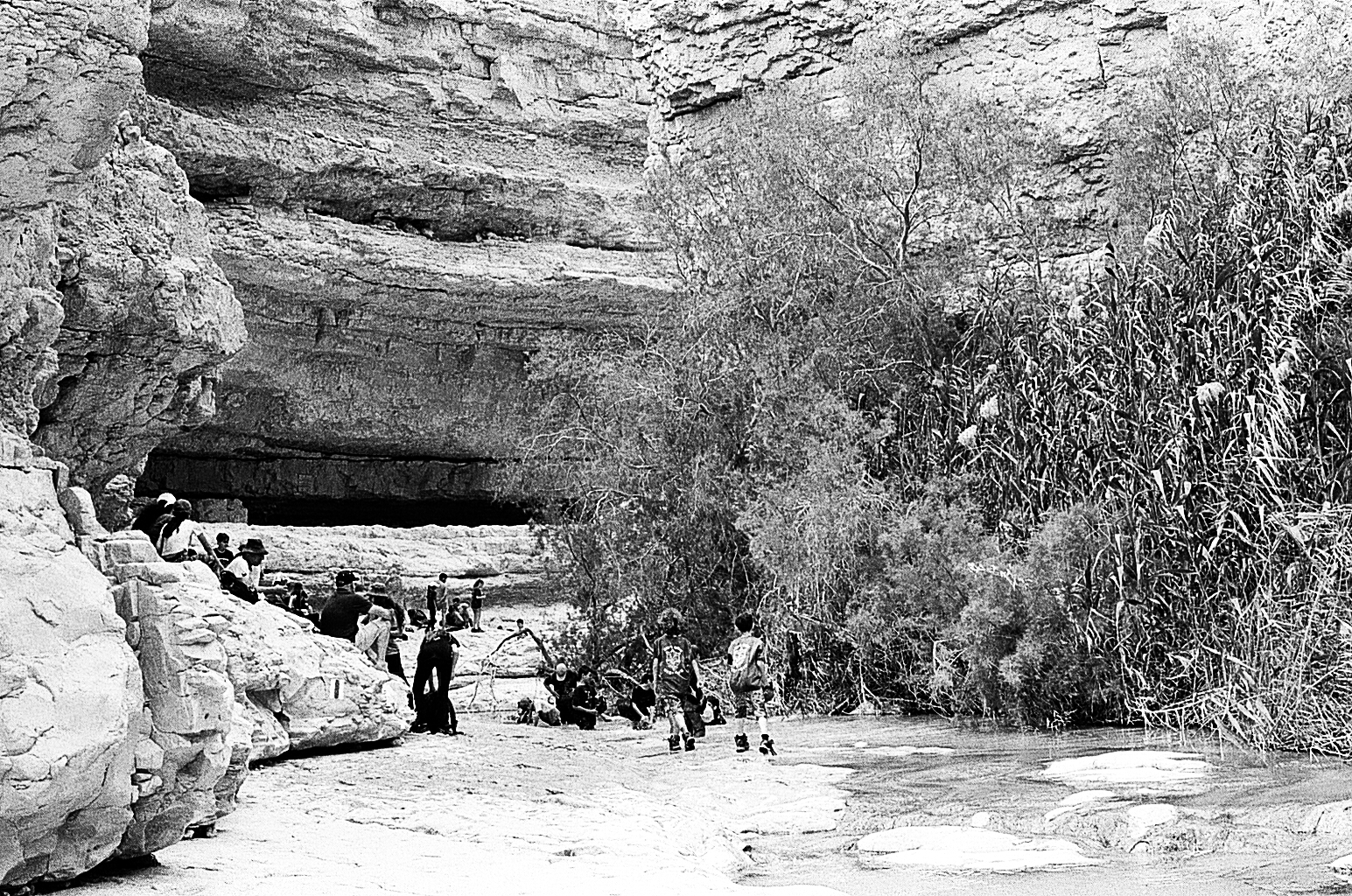

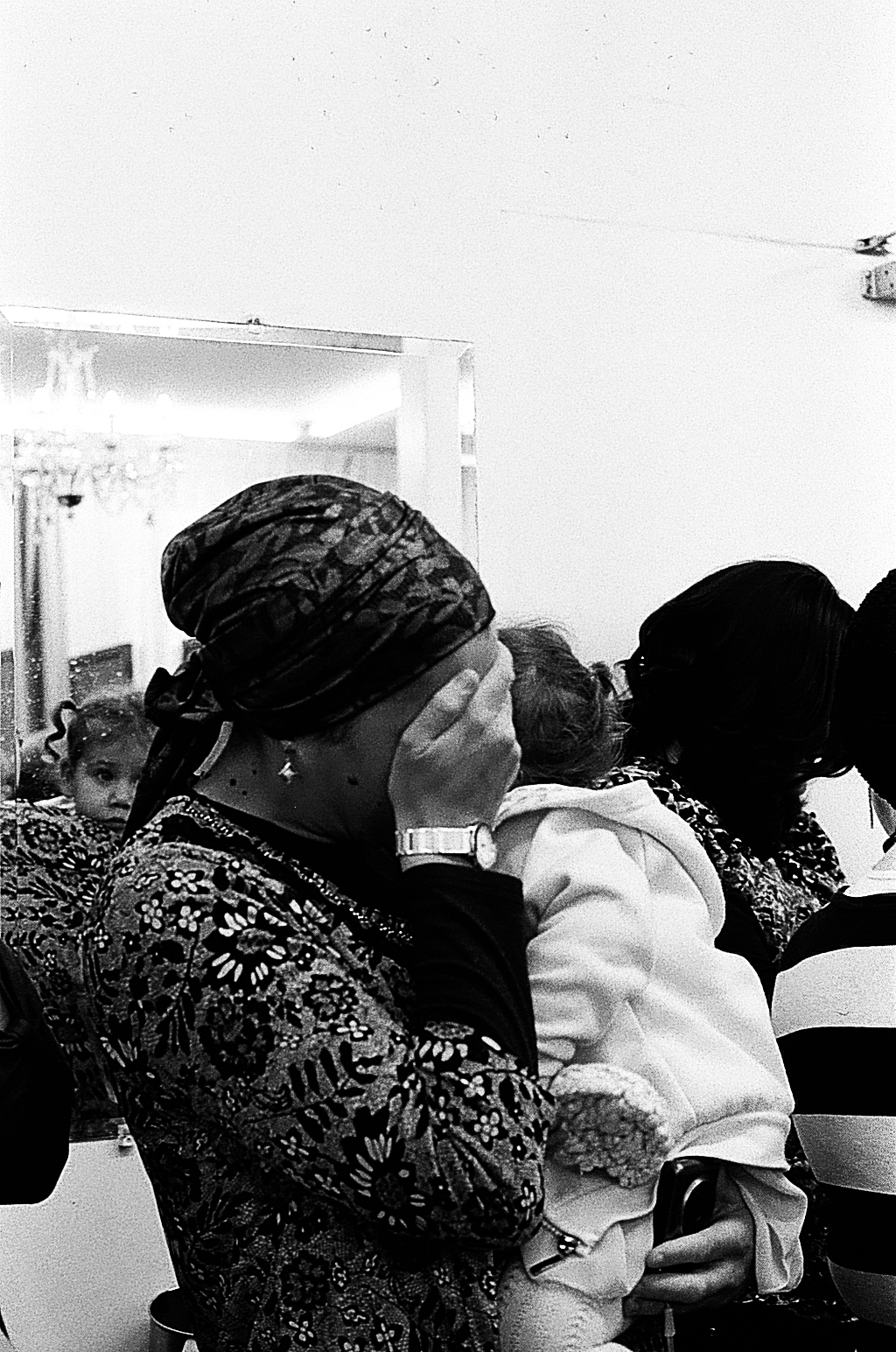

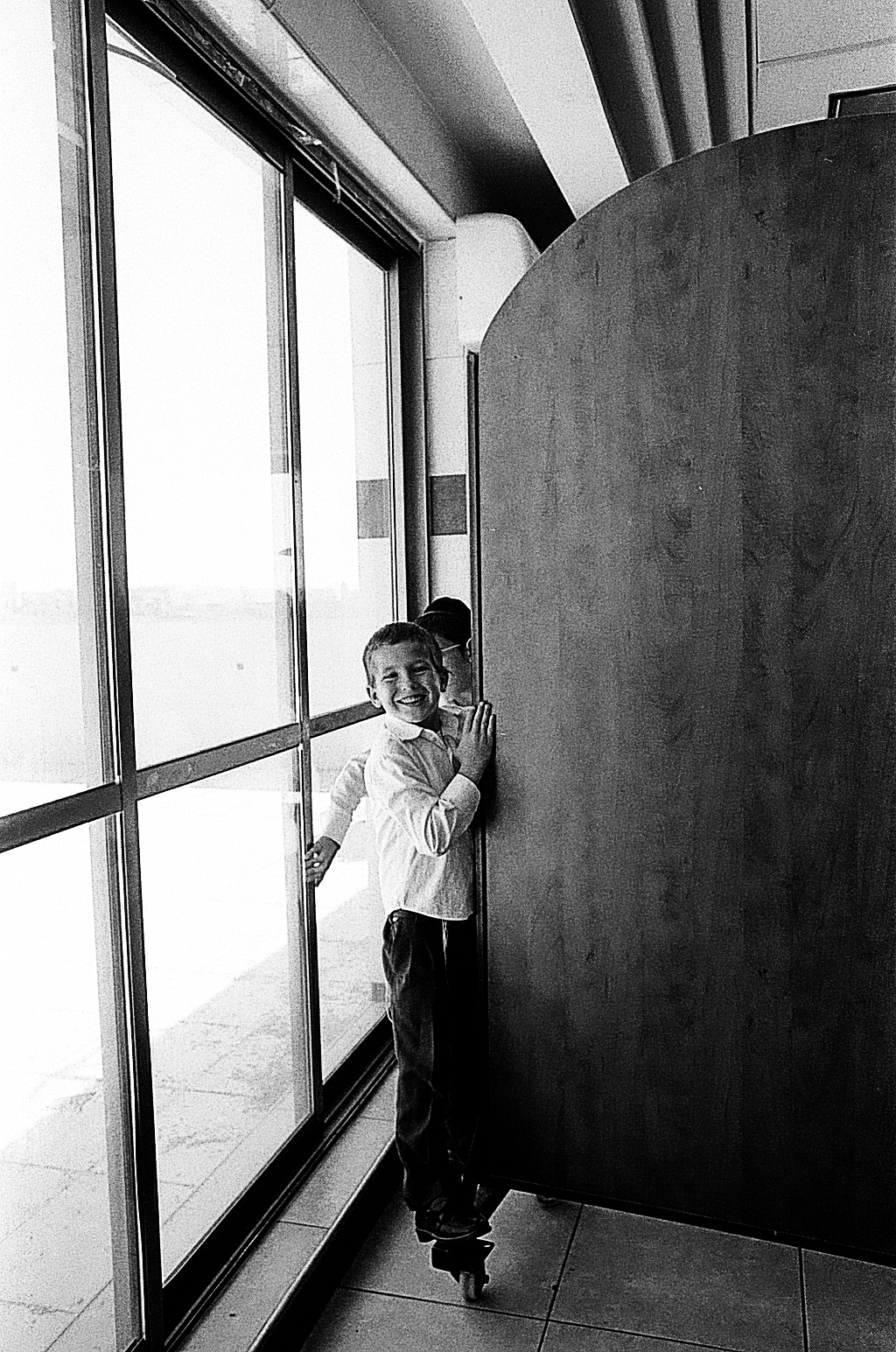

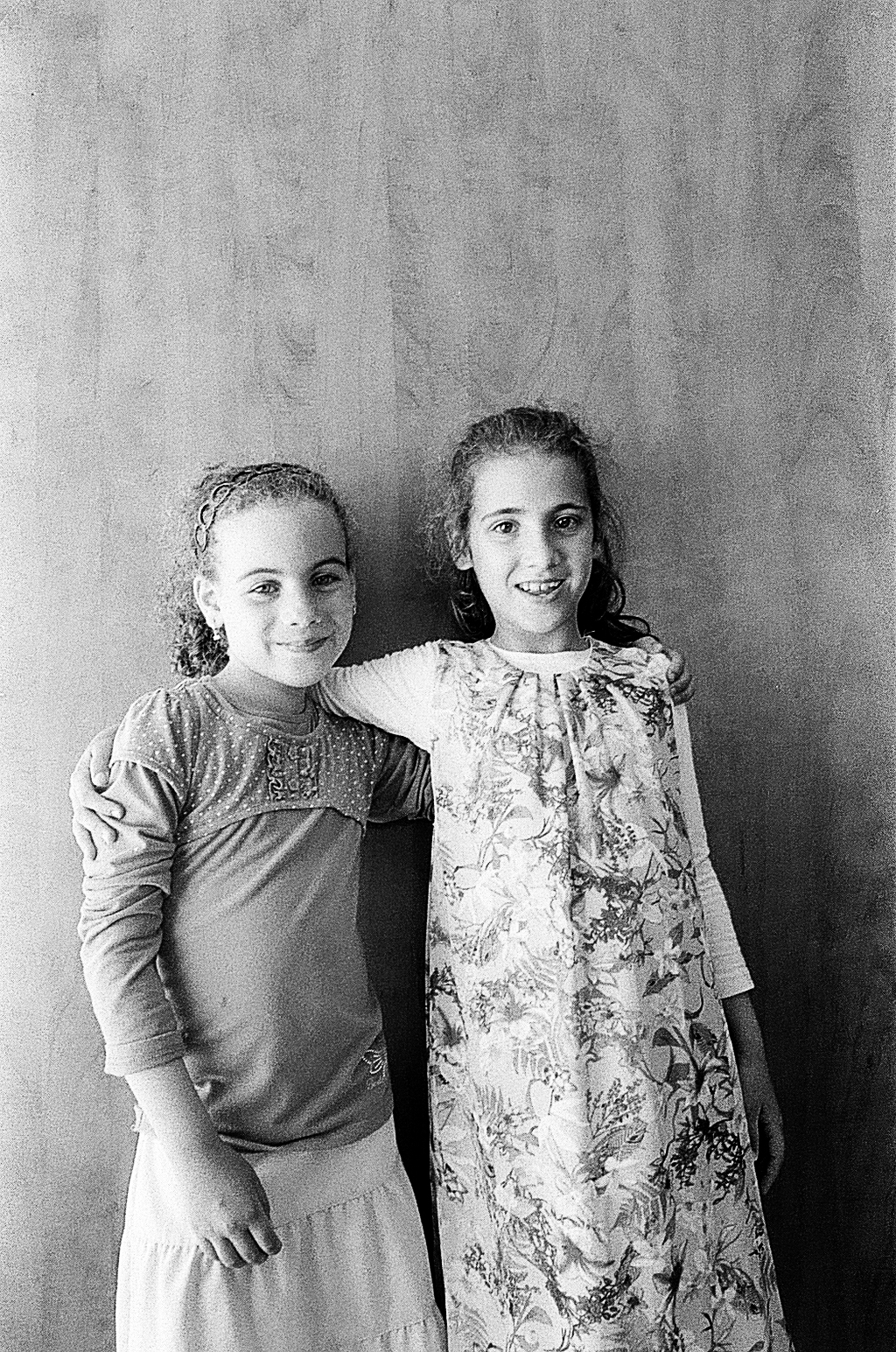

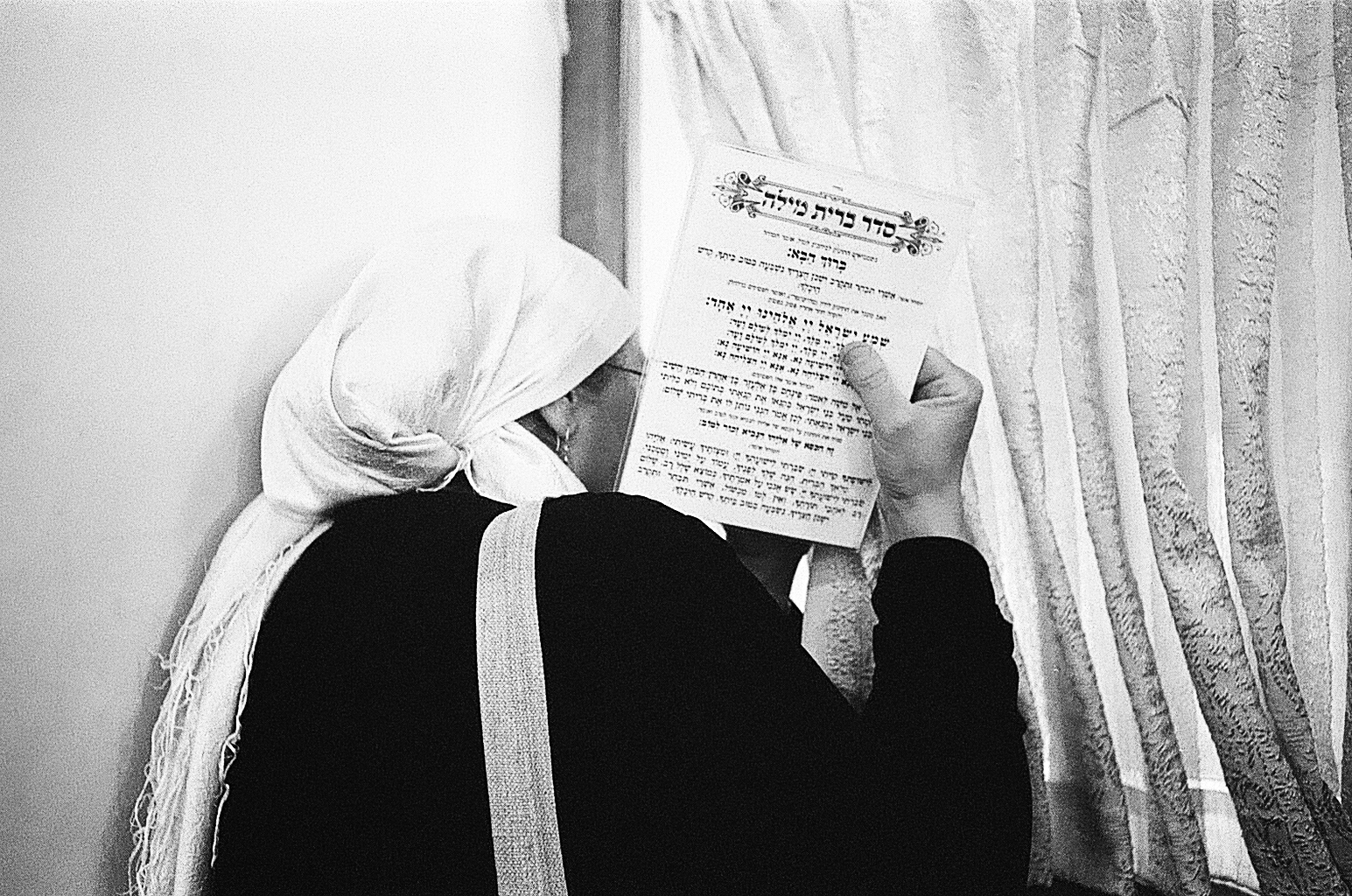

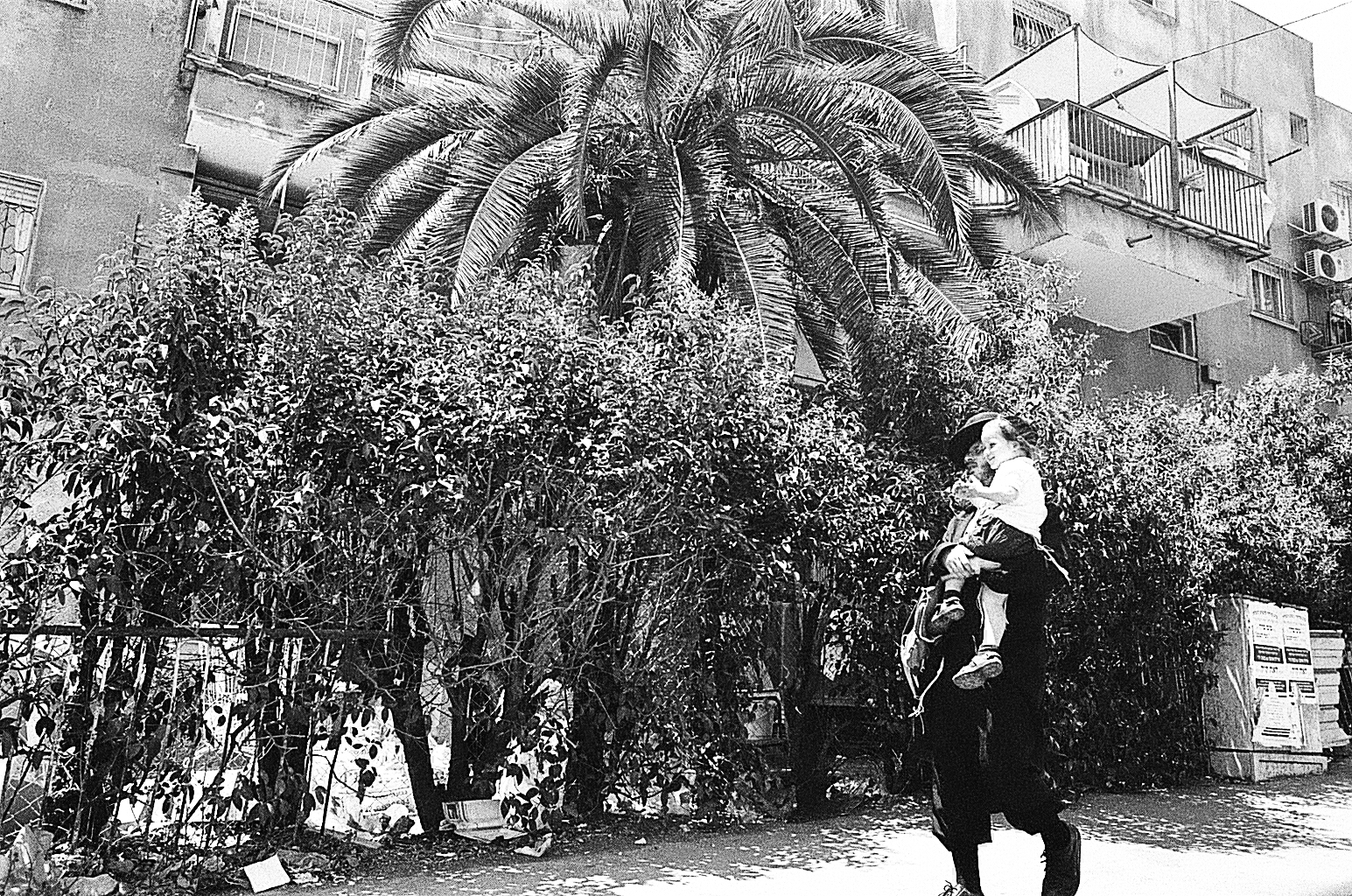

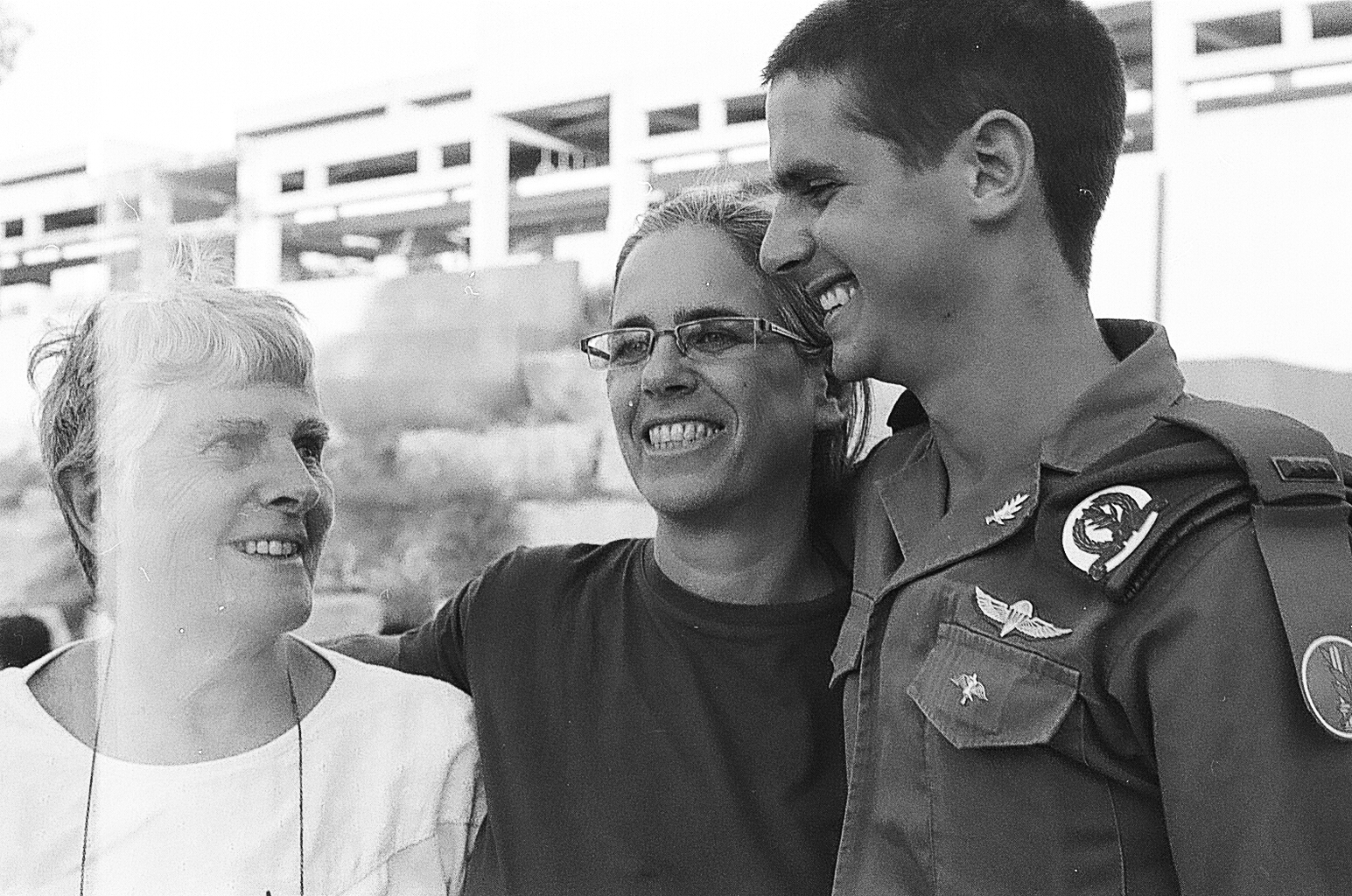

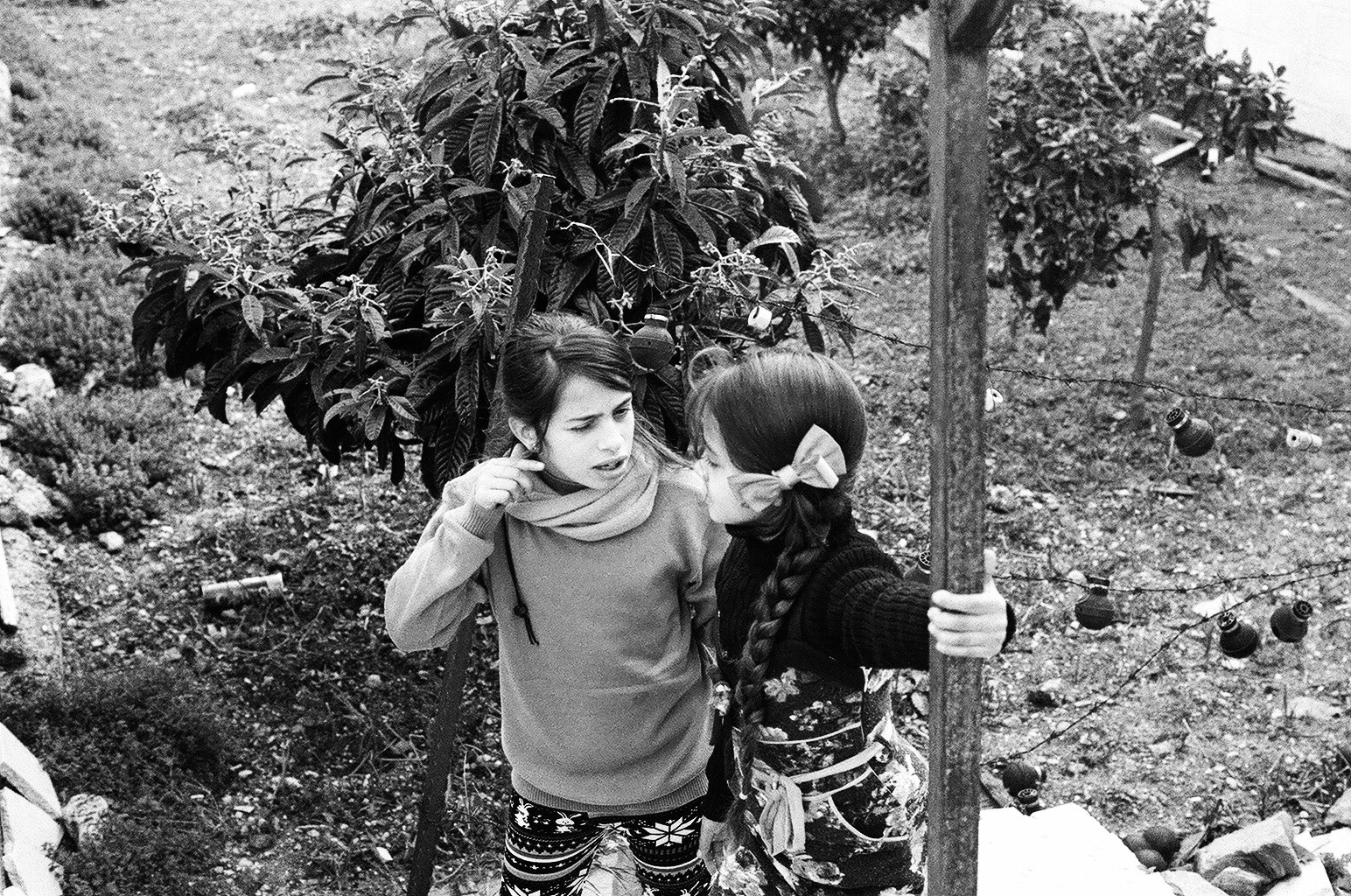

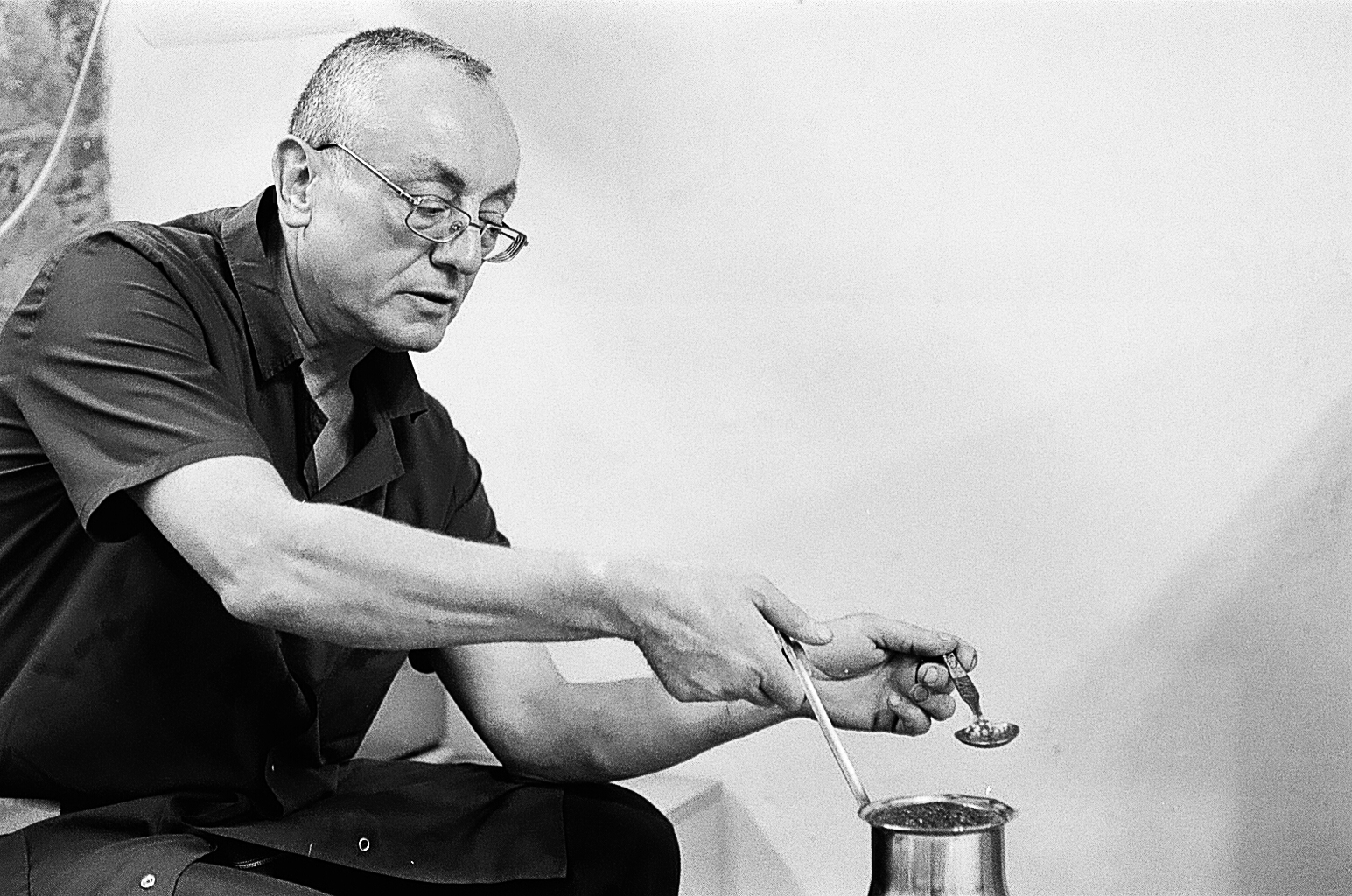

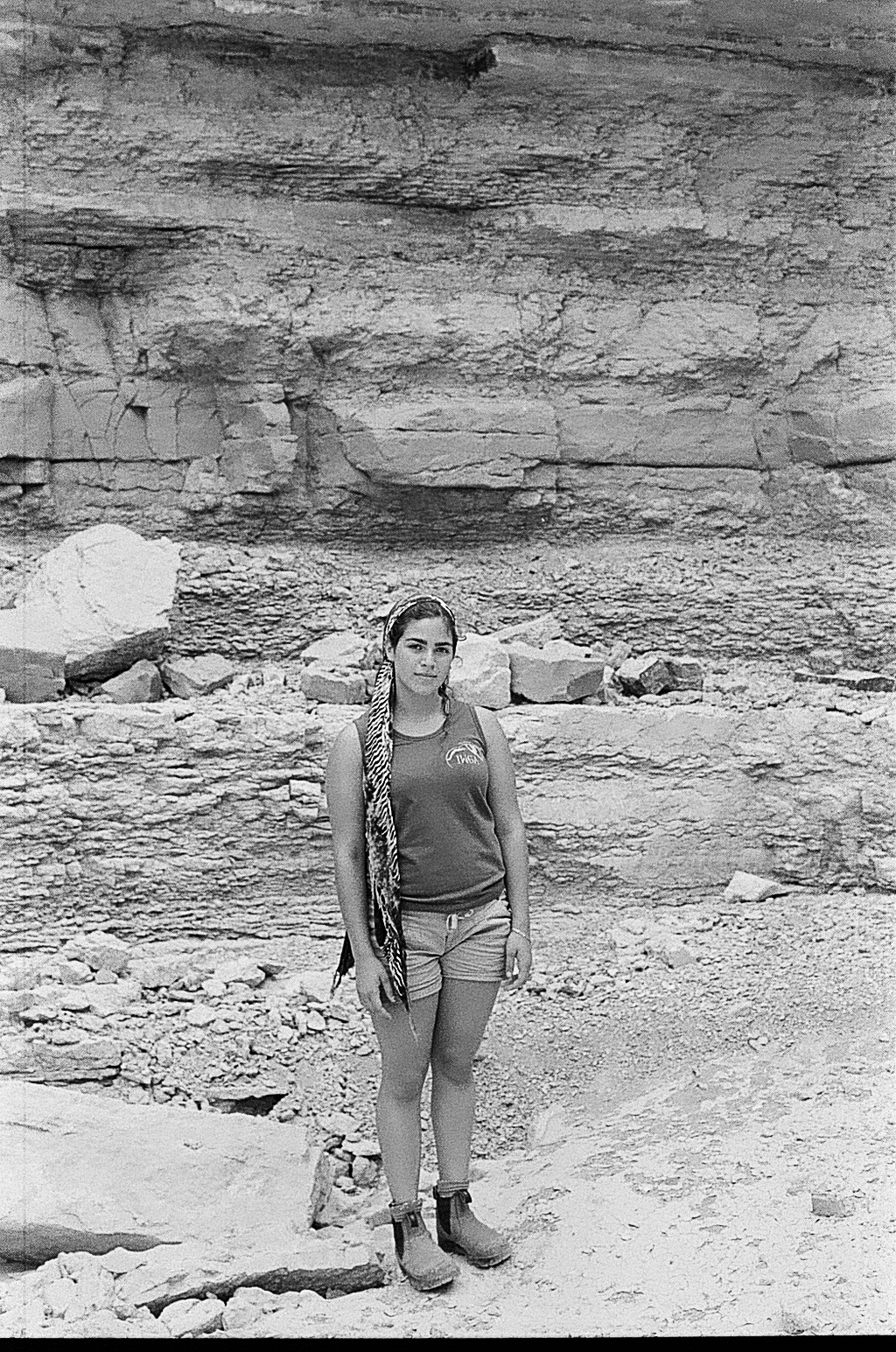

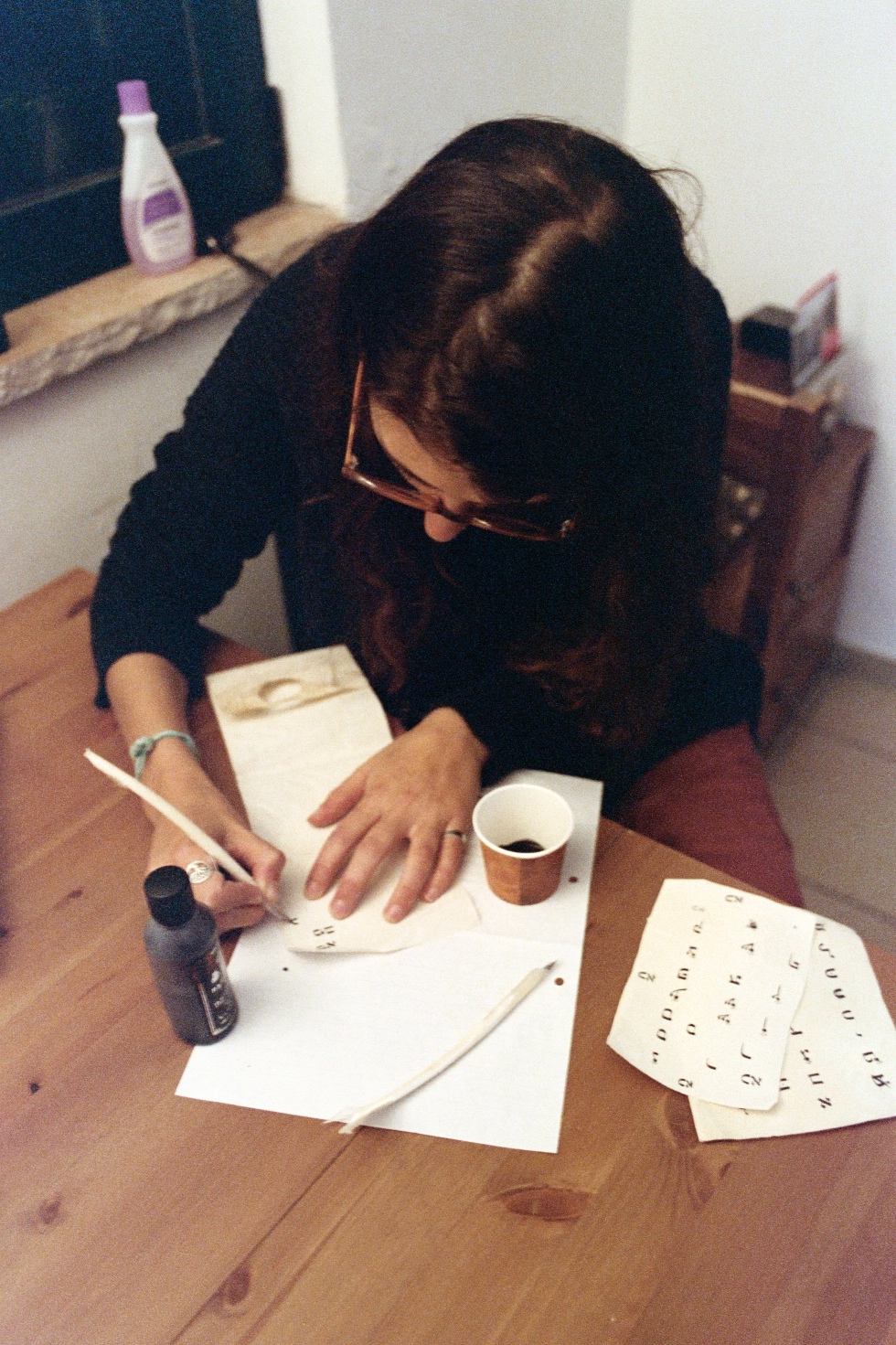

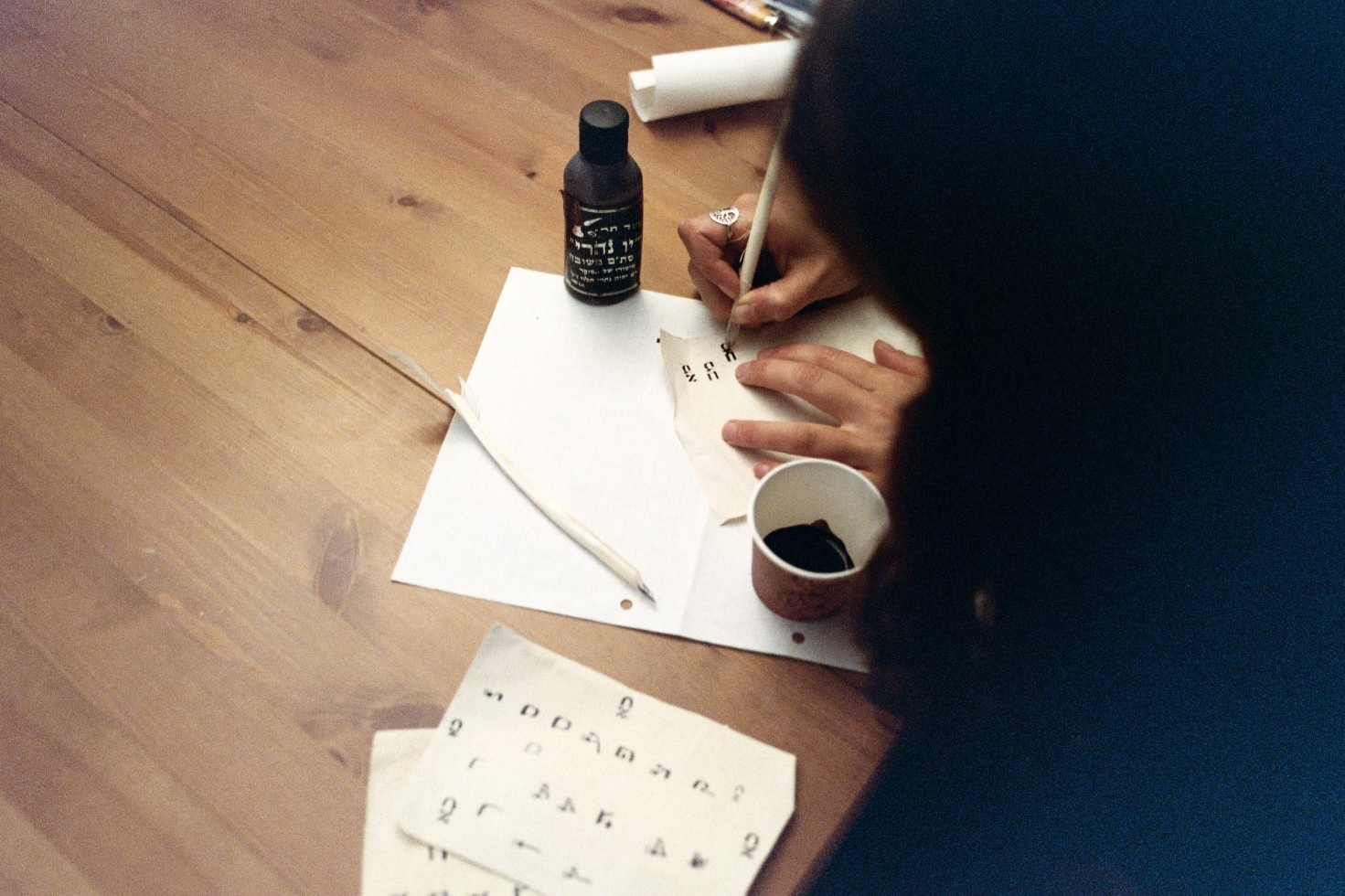

[Here are photos that I took over the course of three years, featuring my view of that Country of Contradictions].